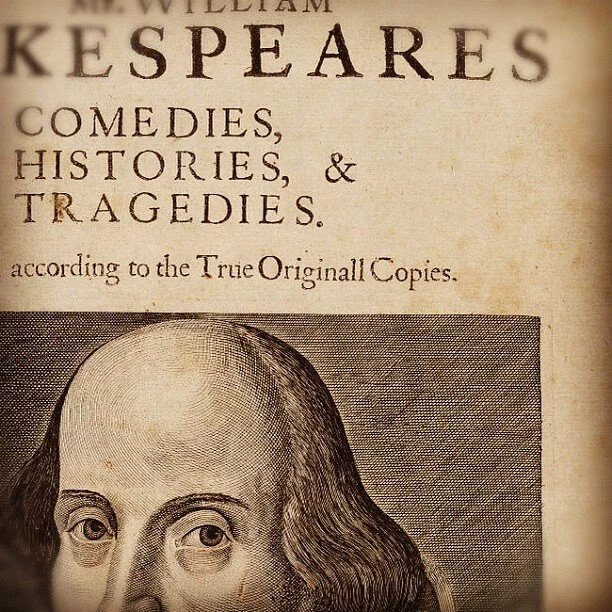

They say it all starts with the inspiration, so I’m fortunate to have the best muse one could wish for – William Shakespeare himself.

They say that this is the fun part, getting inspired, and it certainly is for me, because I get to sit in bed, propped up with pillows, and just read. Rereading Shakespeare takes me back places. Memorable theatre performances… I suddenly remember a school field trip to a Kabuki-style The Tempest performed entirely in Japanese, with the coolest Caliban ever. None of us spoke Japanese, and dare I say it, somehow that made the experience even better – the performance transcended language. I have countless memories of school productions, cinematic experiences, or just periods of solitary reading. Happy memories. They relax me.

But my mind is searching. As I read, I’m subconsciously looking for pieces of a puzzle, something that will fit. I’m thinking about how it feels to be four years old, my daughter’s age, what her life is like, what moves her. I’m looking for a gesture, a sentence, a particular situation in the play I’m reading, when I’ll suddenly have that ‘eureka’ moment and I’ll think, “My daughter would totally get this, if only it weren’t written in iambic pentameter!”

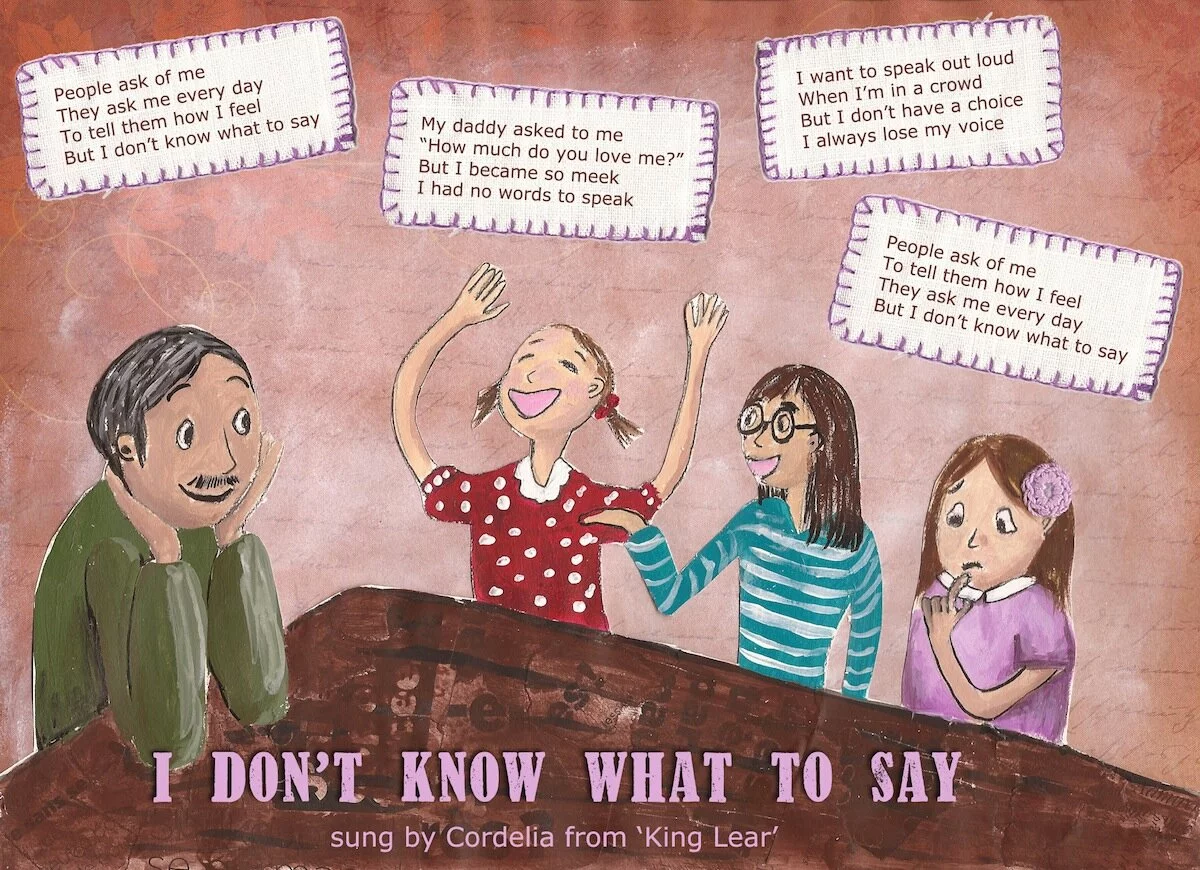

I’m not so presumptuous to I think that my job is making something from nothing. Because it’s already right there, all in the text, in words that were written four hundred years ago. When, in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Helena says, “Sickness is catching: O, were favour so, / Yours would I catch, fair Hermia, ere I go;” I know that children have wondered whether their best friend is more popular, or more beautiful than they. When Beatrice and Benedick bicker in Much Ado About Nothing, I remember that I was once a prurient boy who tried to disguise my curiosity by tormenting the objects of my affection. And even one isolated line like “Alas, poor Yorick! I knew him,” brings back my own fond memories of grandparents and affectionate older friends long gone, and suddenly I’m a child again.

So I’m reading and understanding Shakespeare using everything I’ve learned, all my adult tools, but I’m having to see his words through a child’s eyes, and finally, to express that essence in song, using a child’s words. Once I’m in that childlike state, the song just comes, taking the form of any one of a multitude of nursery rhymes I’ve absorbed over the years, and this completes my creative process.

They say that “All children are artists. The problem is how to remain an artist once he grows up.” Actually, Picasso said that. And in my case, it’s problem solved, because my work takes me back to that childlike state again, and every time, it feels as if the stars are aligned.